It looks like a bombing. Suddenly it rains in my mailbox messages with the message that we are heading for stagflation. The calamity sprang from it, and even one of my best economist friends is in on it.

Google Translated from Dutch to English. Here is the link to the original article in Dutch. The article was originally published on 20 March 2022.

Bad news sells well and you can hardly imagine much worse economic news. Almost everyone immediately understands what is meant. It is a term that leaves little to ambiguity—the 'stag' of stagnation combined with the 'flation' of inflation.

To give the message the maximum amount of drama, most suffice with the simple, short statement that stagflation is ahead of us, after which they let a significant silence fall. No further explanation is considered necessary. Nothing about what it means exactly, how long that disaster will plague us, what it 'means to me,' or what it does to stock markets, for example.

My kids have never experienced stagflation. I do. So if I wanted to, I could tell them from my experience of the calamity that awaits them. It feels like my father telling my brother, sister, and me about the war.

The problem with stagflation is that it is not a tightly defined concept. Of course, it is an extended period of economic stagnation – and thus rising unemployment – combined with persistently high inflation. But how high must inflation be, and how long must it last before stagflation can occur? And how high should unemployment rise? This is not described anywhere, so there is much room for 'poetic freedom.' We experienced it in the 1970s and early 1980s. But that was so long ago that we must dig into the statistics to get an accurate picture.

Stop it

My appeal here is to stop frightening each other. Okay, inflation is high, and the economy may stagnate for a while, but otherwise, the comparison with the 1970s is flawed. In our country, inflation then rose to above 10 percent, and a few years after the inflation peak, unemployment also exceeded 10 percent. It was even worse in the US and the UK.

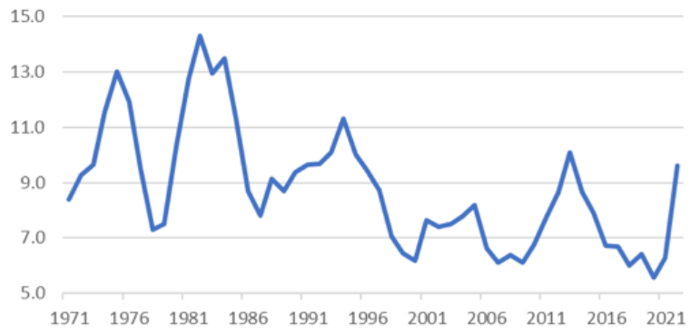

US: Misery index (inflation plus unemployment)

While many economists, and non-economists for that matter, are currently talking about stagflation, I have yet to see anything at all about a measure that became popular at the time but has not yet made a broad comeback: the "misery index." That is a simple sum of the inflation rate and the unemployment rate.

This misery index is a measure of stagflation. A bit of general talk about stagflation is too non-committal for me; to measure is to know. The pictures of the misery index for the US and the Netherlands show what I mean.

US: Misery index (inflation plus unemployment)

(Annual figures, the most recent figure is the monthly figure from Feb. 2022)

A bit of stagflation as a policy strategy?

I'll tell you even more strongly. A little stagflation might be a good idea. We, and for that matter the Americans too, have a very tense labor market. Fed boss Powell even repeated a few times in his press conference last week that 1.7 vacancies per unemployed have never been measured in the US before. Never before has the labor market there been so tight as it is now. What we also often hear is that there is far too much debt in the world.

Regardless of what you think of the latter (I also find that an unnecessary and hopelessly vague – because insufficiently quantified – scare story), you would almost think that a bit of stagflation is the ideal medicine against this combination of shortcomings. The stagnation will lead to some relaxation of the labour market while part of the high debt is 'inflated'.

Now I won't seriously argue that our policymakers deliberately push the economy into stagflation, but to my brethren, I say: “Stop these ominous, vague scare stories. Go do serious analysis.”